In my last stack on early Russian disinformation operations in the United States, I introduced Shakne Epstein, the propagandist that Vladimir Lenin sent to New York in 1921. Esptein’s mission was to found a Yiddish newspaper in the United States—one that would appear to be an organic and unfiltered expression of Lower East Side garment worker community angst, but that in fact circulated Kremlin-approved takes on the labor movement. Lenin aimed to harness the power of the American labor movement and use it to pursue his goals. In the early 1920s, those objectives included the worldwide overthrow of capitalism, of course, but also, incongruously, getting the American government to normalize trade relations with Russia.

So just how does one get to be Lenin’s agitprop man in America?

In the case of Shakne Epstein, the answer would seem to be through bumbling. In his life of 64 years, Shakne managed to rise from the proverbial mailroom of the Jewish socialist party in Poland to become an agent of the Kremlin and a spy for the famed Soviet intelligence service, GRU, an ascent that surprised many of his compatriots. As his colleague in the movement Melech Epstein (no relation) said of him: “Epstein’s ambition far exceeded his limited talent.” He couldn’t hold his liquor, he bragged too much to women, and he talked too much and too often. Yet somehow he survived the twentieth century’s most politically precarious decades without being eliminated, as many of his peers were. His life is worthy of study on those grounds alone, but I believe it holds greater significance for understanding our current situation where we are awash in Russian propaganda that doesn’t look like propaganda, coming from figures we assume to be incapable of such guile.

A Schlemiel is Born

Shakne Epstein. From Leksikonfun der Yidisher Literature, 1927.

As with many socialists in the Russian Empire, Shakne Epstein was hardly a peasant. Born near Vilnius, Lithuania in 1883, he was descended from a family of rabbis. As a young man he moved to Warsaw, initially planning to be a painter. He became a socialist instead, joining the famous Jewish socialist party, the Bund, in 1903. Caught taking part in the 1905 attempted revolution against the tsar, he was arrested and imprisoned. Released within months, he was arrested again in 1906 and sentenced to two years in a camp in the Volograd region. Epstein escaped the compound within three months, however, and fled to Vienna. In 1909, he traveled to America where he became one of the co-founders of the Jewish Socialist Federation.

Jewish Socialist Federation. Shakne Epstein standing, left.

Shakne worked in America for various newspapers until in 1913 he became editor of Gleichheit (Equality), a journal for the International Ladies Garment Worker Union. At the time of editorship, the ILGWU was one of the most powerful unions in the country. On the heels of the horrific 1911 Triangle Fire in which 146 garment workers, mostly young Jewish and Italian women, died tragically and needlessly, union membership had boomed. Shakne began an affair with one woman in the movement, Juliet Stuart Poyntz, who he radicalized. She will emerge as a person of significance later in this tale.

Revolution…Finally!

Socialists like Shakne who had fled the Russian empire spent their days in America waiting for a sign that the revolution was imminent back in their homeland. When in 1917 it looked as though the latest wave of proletarian unrest might finally succeed in toppling the tsar, Epstein picked up his wife and son and moved back to Russia to join the fight. According to Melech Epstein, Schakne was originally against Lenin but quickly changed sides when he realized which way the wind was blowing. Upon Lenin’s ascension to power, he split from the socialist party and officially joined the Russian Communist Party.

For three years he honed his skills running communist propaganda newspapers in Bolshevik Russia. Having proved his ability to churn out print with the correct slant, in 1921 he was sent back to the United States with a mission.

Lenin had long found the situation in America vexing. There were two major communist parties in the United States, and they were constantly bickering with one another. This the new leader of the world’s communist parties found infantile and ineffective. Acting through the Comintern (the organization which dictated policy to communists worldwide), Lenin ordered the two American parties to unify which they did in a secret convention at the remote Overlook Hotel in the Catskill mountains in May 1921 .

In all likelihood, Epstein had been the one to propose the location for this historic meeting. The Overlook Hotel had been the summer vacation house of the International Ladies Garment Worker Union just a few years before. The vacation bookings were managed by Poyntz, his girlfriend in the union. The Overlook was difficult to get to, poised at the top of a mountain above Woodstock with only one road leading in and out of it.

It wasn’t as clandestine a place to meet as the communists had thought. The Bureau of Investigation (fore-runner of today’s FBI) had a man on the scene to report on the creation of the Unified Communist Party. This agent noted the cloak and dagger atmosphere of the gathering: “Supplies were brought to the hotel in a wagon drawn by guards of the hotel. At night these guards would signal by flashlight to each other from various mountain tops that everything was OK.”

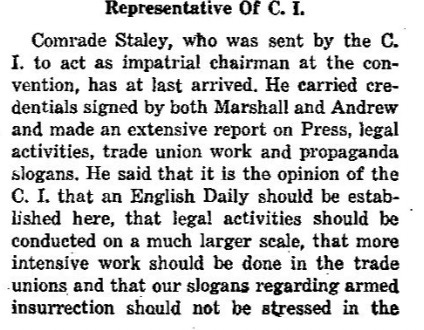

According to the Communist Party of America bulletin, Shakne Epstein (referred to as his alias, Arthur Staley) was supposed to have been the chairman of this momentous gathering. He had been delayed in his journey, however, and missed the convention entirely. Total schlemiel move.

It was June when Shakne, under his alias Staley, marched into a meeting of the Central Executive Committee of the Communist Party of America [CPA], submitted his credentials as a representative of the Comintern, and announced he was there to found a newspaper.

Party Poopers

It took the better part of a year to get the agitprop Yiddish daily up and running. First, funding from the Kremlin was delayed. Then, fighting within the Jewish federation of the CPA had to be quelled. Finally, in 1922, the Freiheit (“Freedom”) hit the presses and proceeded to seed division at the heart of the American labor movement.

The Freiheit worked a little like a Yiddish Fox News, but instead of retirees in Florida, its target audience was the Jewish garment workers of the Lower East Side. It told workers that the leaders of their unions were living high off the hog—and on worker dues! It told them that workers should not be bargaining with their employers—they should be seizing the means of production for themselves! If they were really for revolution, they should stop their union leadership from colluding with the capitalist bosses!

Typical of the Freiheit’s angle was this cartoon, which depicts the diminutive president of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, Morris Sigman (in the tuxedo) throwing his arm around the portly dressmaker’s boss.

By all accounts, Shakne Epstein was a hard worker, sometimes writing his articles late into the night. But after more than a year of toiling anonymously for the Freiheit (he was unable to publish only his own name because of his illegal status as an underground agent for the party) Epstein became dissatisfied. He had attended several meetings with the CPA leadership in the first months after his arrival, but now he was shut out. He felt he was owed him money, which he was rapidly running out of. The final straw was when he was not offered a meeting with a representative of the Comintern visiting American party leadership in the fall of 1922.

He wrote a searing letter to the CPA leadership voicing his outrage:

Just consider how ridiculous is the situation: I am active in the Jewish labor movement for the last twenty years. Have always occupied a prominent place in the movement in Russia as well as in America….The Comintern sends me on the strength of my record to America for general party work and specifically for Jewish work. And in spite of all this, contrary to all logic, the CEC [Central Executive Committee] of the CPA ignores me to such an extent.

He signed the letter, Arkadeiff—yet another alias. (He had at least 8 aliases that I am aware of.)

The men at the top of the Communist Party of America could not believe his nerve. To be fair, they were all as preening and vain as Shakne was. They responded to his letter—but not directly to him. Instead they sent their reply to the leadership of the Jewish federation of party, asking them to get Shakne under control:

He believes that he is not under the discipline of the American Party. That is sheerest nonsense…The CI gave him no special mission in America, but only sent him on party work, and especially Jewish work. It is time to put an end to the foolish legend that having been given a credential, Com. Arkadieff had any further mission to perform for the CI. Please inform Com. Arkadieff that he either must work under the discipline of the Party or there will be no room for him in the American Party.

In an extra slap down, they pointed out that the representative of the Comintern hadn’t asked to see Shakne, so that wasn’t their fault, was it.

Shakne was no doubt deeply offended by this response, but he fell in line enough to keep his job at the Freiheit.

He clearly never forgot the incident, though. In 1925, he was presented with an opportunity to tell his side of the story. To commemorate the first anniversary of Lenin’s death, the Freiheit published a series of articles about the great leader. Epstein’s contribution ended with a lengthy account of his being summoned to the Kremlin to meet with Lenin personally years in 1921. Lenin, he said, had requested his opinion of the American Communist movement, including an evaluation of its leaders. Epstein’s account was larded with details that would suggest that he was an insider. He described the grandeur of the Kremlin’s hallways with their high Venetian windows, his overhearing Trotsky in an adjoining room as he waited for his appointment, Lenin’s relaxed demeanor as they spoke, and even a chance meeting with the great writer Gorky as he exited Lenin’s office.

The audience for this account was no doubt his enemies in CPA leadership, as he mentioned Lenin’s disdain for those American communists who hid in the shadows planning armed revolution. Lenin, he reported, said, “the smallest legal newspaper is much more important than a big secret organizational apparatus.”

Shakne Epstein “Lenin at Home and Abroad.” Freiheit, 1925.

Take that, CPA! But by 1925, the CPA was gripped by a leadership crisis, so likely nobody took great notice of Shakne. Unable to rise within the American party, Shakne returned to Russia in 1927.

Into Stalin’s Grip

The Russia that Shakne returned to was much different from the Russia he had left six years before. Stalin had taken charge and had little use for Shakne. Shakne tried to ingratiate himself to the new leader by publishing a book of flattery. In it, he declared that Stalin was the true heir to Lenin’s Russia. This was a grave mistake. He had in doing so insinuated that Lenin’s conception of Bolshevik Russia was primary and Stalin was merely following through with the plan.

Displeased by the book (the flaws of which were advertised widely by Shakne’s enemies), Stalin banished Shakne to Siberia for a few years.

To get out of exile, Shakne offered to spy for GRU. What he did for Soviet intelligence is not fully known but one detail is: In 1937, he walked his former lover, Juliet Stuart Poyntz (who had herself become a spy for Russia but was of late threatening to expose intelligence secrets) into the hands of a GRU hit squad.

Surprisingly, serving up his former lover to GRU would not be the worst thing Shakne Epstein would ever do. Back in Moscow during World War II, he had been made executive secretary of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee—essentially a show committee Stalin established to make the Soviet Union look like the opposite of Nazi Germany. Unfortunately for them, the members of the committee took their jobs seriously. In 1944, they signed a letter decrying increasing antisemitism and suggesting that Jewish refugees be allowed to settle in Crimea. Although Epstein signed this letter as well, he was also reporting on the committee’s plans to Russia’s internal intelligence unit, the NKVD.

Stalin, his paranoia and anti-Semitism ever increasing as he aged, viewed the committee’s letter as treason. He imprisoned all the committee members and put them on trial, executing all but one in 1952.

Unlike his fellow committee members, Shakne Epstein was never arrested and nor was he put on trial. He died of a brain aneurysm in 1945. Or so it is said. I hope by this point in this series on Russian disinformation, we realize that we never really do know.

Selected sources

Epshteyn, Shakhne https://congressforjewishculture.org/lexicon/t/2278.

Epstein, Melech. The Jew and communism; the story of early Communist victories and ultimate defeats in the Jewish community, U.S.A., 1919-1941. New York, Trade Union Sponsoring Committee 1959.

Rezen, Zalman. Leksikonfun der Yidisher Literature, Prese Un Filologye. (1927) Amherst, MA: National Yiddish Book Center. https://www.yiddishbookcenter.org/collections/yiddish-books/spb-nybc200691/rejzen-zalman-leksikon-fun-der-yidisher-literatur-prese-un-filologye-vol-2

As Arte Johnson so often said: verrrry interesting